Hola amigos de nortonteatro.blog. Yo soy Nortan Palacio, conocido artísticamente y entre bobos, como Norton P.

Hello friends of nortonteatr.blog. I am Nortan Palacio, known artistically and between stupids as Norton P.

Sábado 27 de abril 2024.

ENGLISH VERSION. BELOW SAPNISH VERSION

ANÉCDOTA 104

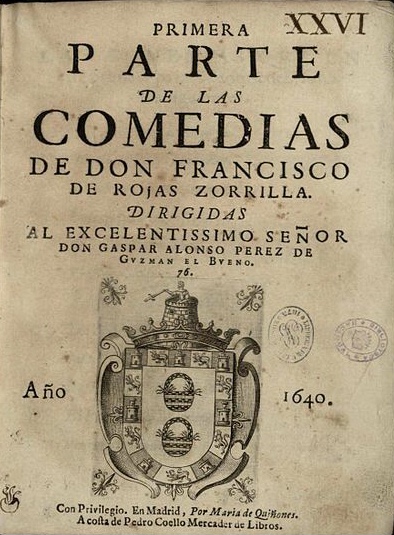

FRANCISCO DE ROJAS ZORRILLA

UN SEGUNDÓN DE PRIMERA II.

En la pasada anécdota te hablaba de la vida de Rojas Zorrilla y dejaba para esta el repaso de su obra teatral y aquí te la voy a resumir.

Lo primero que hay que decir es que, a pesar de que siempre se ha considerado a Rojas Zorrilla como seguidor de Calderón; está consideración está bastante lejos de la realidad. Porque aunque «formalmente» podemos decir que lo imitaba: usando un lenguaje culterano y conceptista[1] y una estructura que moldeaba el ímpetu de la acción (ya moderado, ya exacerbado) por el despliegue retórico; «en el fondo» Rojas Zorrilla fue un gran innovador, lo que pasa es que hasta hace poco, que se ha puesto de relieve el estudio de su obra, esas innovaciones habían quedado acalladas. De cualquier manera, la investigación está mostrando que, en su momento, el público sí que percibía tales innovaciones.

Cuáles eran tales innovaciones: en las tragedias (dramas de honor) al contrario que en los de Calderón, las mujeres adquirían mucha más relevancia, por ejemplo: si eran deshonradas no acudían al marido, padre o hermano a buscar el reparo de su honra, sino que ellas mismas tomaban sus revanchas; y en el caso de que los maridos les fueran infieles, ellas (al contrario que los caracteres masculinos de El médico de su honra, o El pintor de su deshora de Calderón) eran las que buscaban las maneras de aplicar la «ley de talión» contra los maridos: ejemplos de estas son: Morir pensando en matar, Los encantos de Medea, Progne y Filomena, Los áspides de Cleopatra, etc., que, como se aprecia, bebía más de las tragedias senequistas[2] que de los dramas calderonianos.

Sin embargo, estas innovaciones, aunque eran percibidas por los asistentes a los Corrales de Comedias no siempre eran bien recibidas En algún caso, como en el estreno de Cada cual lo que le toca, el público silbó la obra porque la protagonista, después de ser deshonrada y de vengarse de su agresor, es perdonada por su marido y reaceptada en el matrimonio. Esto, no se había visto en escena, porque la mujer deshonrada nunca era perdonada, aunque no tuviera culpa de su deshonra.

De las innovaciones en lo cómico, la primera que siempre se menciona es la de la creación de un nuevo subgénero: la Comedia de Figurón con la más famosa de ellas: Entre bobos anda el juego, que nos pinta a Don Lucas del Cigarral, como un personaje extravagante, prepotente, orgulloso de su incultura, pero que se cree a sí mismo impresionante y que todo el mundo debe admirarle. Estos ragos extravagantes (a veces afeminados, a veces maleducados, otras veces a la usanza antigua) pero siempre orgullosos de sí mismos, pasaron a otros personajes de algunas comedias y alcanzaron el cenit en El lindo don Diego, de Agustín Moreto, y entre medias recrearon el dicho subgénero.

El hecho de que la extravagancia del personaje obligaba al autor a dibujarlo con rasgos específicos, recreó también la innovación: ahora estos personajes dejaban de ser esterotipos y pasaban a tener rasgos psicológicos (aunque extravagantes) definidos, es decir; se hacían seres humanos. Esto, aunque ahora parezca algo natural, en esa época sentó un precedente, y puso a Rojas Zorrilla como autor favorito de los autores de comedias de carácter del siguiente siglo tanto en España y en el resto de Europa donde fue muy imitado.

Por otro, lado el humor que utilizaba Rojas Zorrilla en sus comedias era mucho más descacharrante (casi que rayando en el estilo de los entremeses o las comedias burlescas) que el fino humor de Calderón[3], y esto también le marcaba su propio estilo a nuestro autor, porque este humor no se rebajaba al humor entremesil, precisamente por los rasgos psicológicos de los peronajes. Una de las muestras más patente de este particular estilo se encuentra en la desternillante comedia: Abre el ojo.

Finalmente, y para que veas por qué lo podemos considerar un autor de primera fila, hay que señalar que la continuidad del Teatro Barroco en el siglo XVIII se redujo a pocos autores del siglo XVII: claro está Lope, Tirso y Calderón, pero hay que señalar que Rojas Zorrilla en algunos momentos llegó a superar a este trío y se sabe que en este nuevo siglo, solo en Madrid, se realizaron 654 montajes de nuestro autor.

Además, en un afan de preservar las obras maestras del ya denominado Teatro Clasico, el ministro y capitan general de Castilla la Nueva, el Conde de Aranda (quien era un gran seguidor de la ilustración), encomendó a su secretario de estado Bernardo de Iriarte a leerse seiscientas comedias del siglo anterior para salvar las que tuvieran mejor compostura, mayor enjundia y modernidad (es decir querían crear el primer canon del Teatro del Siglo de Oro). Se sabe que Iriarte salvó veintiun comedias de Calderón, once de Agustín Moreto y en tercer lugar (por delante de Lope y de Tirso) puso a Rojas Zorrilla con siete comedias: Abre el ojo, Entre bobos anda el juego, Casarse por vengarse, Sin honra no hay amistad, Lo que son las mujeres, No hay amigo para amigo y Donde hay agravios no hay celos.

Pero, además de estas y otras obras que he ido nombrando a lo largo de la anécdota hay que señalar como excelentes entre otras: Del rey abajo ninguno, El caín de Cataluña, Obligados y ofendidos, El mejor amigo: el muerto, Persiles y Sigismunda (basada en la novela de Cervantes), Numancia destruida (casi como una continuación de El cerco de Numancia, también de cervantes), El robo de las sabinas, Lo que son las mujeres, etc.

Lastima que en el siglo XIX Rojas Zorrilla cayera en un injusto olvido que lo hizo apearse del canon y hoy tenga que seguir luchando (con la inestimable ayuda, como dije, de los investigadores de la Universidad de castilla la Mancha: Felipe Pedraza y Rafael Gonzalez Cañal) para recuperar su lugar. Estamos seguros de que lo recuperará.

Y a ti, amigo lector, espero recuperarte siempre en mis proximas anécdotas.

[1] Aunque ese tipo de formas las habían impuesto Góngora y Quevedo, respectivamente, en lo referente a la poesía; fue Calderón el que lo adaptó a las formas teatrales con gran magisterio y por eso a quien lo usaba se le consideraba seguidor

[2] Las tragedias de Séneca habían estado de relieve en el siglo XVI en España, pero en el XVII, después de Lope de Vega y Calderón, habían sido olvidadas; esta recuperación por parte de Rojas Zorrilla, también hizo de él un innovador, combinando lo formal de Calderón con los episodios realmente trágicos de las heroínas de Séneca.

[3] Es como si en el siglo pasado compararmos el humor de Woody Allen con el de Mel Brooks.

ANECDOTE 104

FRANCISCO DE ROJAS ZORRILLA

A SECONDED OF FIRST-CLASS 2.

In the last anecdote I told you about the life of Rojas Zorrilla and I left for this one the review of his theatrical work, and here I am going to summarize it for you.

The first thing to say is that, despite the fact that Rojas Zorrilla has always been considered a follower of Calderón, this consideration is quite far from reality. Because although «formally» we can say that he imitated him: using a cult and conceptualist language[1] and a structure that molded the impetus of the action (already moderated, already exacerbated) by the rhetorical deployment, «formally» Rojas Zorrilla was a great innovator, what happens is that until recently, when the study of his work has been highlighted, These innovations had been silenced. Either way, research is showing that, at the time, the public did perceive such innovations.

What were these innovations: in the tragedies (dramas of honor) unlike in Calderón’s, women acquired much more relevance, for example: if one woman was dishonored, she did not go to her husband, father or brothers to seek reparation for her honor, but they themselves took their revenge; and in the case that her husband was unfaithful to her, she (unlike the masculine characters in Calderón’s The Doctor of His Honor, or The Painter of His Time) was who looked for ways to apply the «law of talion» against her husband: examples of these are: Dying thinking about killing, The charms of Medea, Progne and Philomena, Cleopatra’s asps, etc., who, as can be seen, drank more from the tragedies of Senequis[2] than from Calderon’s dramas.

However, these innovations, although perceived by the attendees of the Corrales de Comedias, were not always well received. In some cases, such as in the premiere of Cada cual lo que le toca, the audience whistled the play because the protagonist, after being disgraced and taking revenge on her aggressor, is forgiven by her husband and reaccepted into marriage. This had not been seen on the scene, because the disgraced woman was never forgiven, even if she was not to blame for her dishonor.

Of the innovations in comedy, the first that is always mentioned is the creation of a new subgenre: the Comedia de Figurón with the most famous of them: Entre bobos anda el juego, which paints Don Lucas del Cigarral, as an extravagant, arrogant character, proud of his lack of culture, but who believes himself impressive and that everyone should admire him. These extravagant ragos (sometimes effeminate, sometimes rude, other times old-fashioned) but always proud of themselves, passed to other characters in some comedies and reached the zenith in El lindo don Diego, by Agustín Moreto, but in between they recreated the aforementioned subgenre.

The fact that the extravagance of the character forced the author to draw him with specific traits, also recreated the innovation: now these characters ceased to be stereotypes and began to have defined psychological (although extravagant) traits, that is; they became human beings. This, although it now seems natural, at that time set a precedent, and made Rojas Zorrilla one of the favorite author of the authors of Character Comedies in Spain and in the rest of Europe where he was much imitated.

On the other hand, the humour that Rojas Zorrilla used in his comedies was much more bizarre (almost bordering on the style of Entremeses or Burlesque Comedies) than Calderón’s fine humour[3], and this also marked our author’s own style, because this humour was not reduced to the humour of the intermesile, precisely because of the psychological traits of the people. One of the most obvious examples of this particular style is found in the hilarious comedy: Abre el ojo (Open Your Eye).

Furthermore, and so that you can see why we can consider him a first-rate author, it should be noted that the continuity of the Baroque Theatre in the eighteenth century was reduced to a few authors of the seventeenth century: of course there is Lope, Tirso and Calderón, but it must be pointed out that Rojas Zorrilla at times came to surpass this trio and it is known that in this new century, In Madrid alone, 654 productions of our author were made.

In addition, in an effort to preserve the masterpieces of the so-called Classical Theater, the minister and captain general of New Castile, the Count of Aranda (who was a great follower of the Enlightenment), commissioned his secretary of state Bernardo de Iriarte to read six hundred comedies from the previous century to save those that had the best composure. greater substance and modernity (i.e. they wanted to create the first Canon of the Theatre from Spanish Golden Age). It is known that Iriarte saved twenty-one comedies by Calderón, eleven by Agustín Moreto and in third place (ahead of Lope and Tirso) he put Rojas Zorrilla with seven comedies: Abre el ojo, Entre bobos anda el juego, Casarse por vengarse, Sin honra no hay amistad, Lo que son las mujeres, No hay amigo para amigo and Donde hay agravios no hay celos.

But, in addition to these and other works that I have been naming throughout the anecdote, we must point out as excellent among others: From the King Down None, The Cain of Catalonia, Obliged and Offended, The Best Friend: The Dead Man, Persiles and Sigismunda (based on the novel by Cervantes), Numancia destroyed (almost as a continuation of The Siege of Numancia, also by Cervantes), The Theft of the Sabine Women, What Women Are, etc.

It is a pity that in the nineteenth century Rojas Zorrilla fell into an unjust oblivion that made him disembark from the Canon and today he has to continue fighting (with the invaluable help, as I said, of the researchers of the University of Castilla la Mancha: Felipe Pedraza and Rafael González Cañal) to recover his place. We’re sure he’ll get it back.

And to you, dear reader, I hope to always recover you in my next anecdotes.

[1] Although this type of form had been imposed by Góngora and Quevedo, respectively, in terms of poetry; it was Calderón who adapted it to theatrical forms with great mastery and that is why those who used it were considered followers

[2] Seneca’s tragedies had been prominent in sixteenth-century Spain, but in the seventeenth, after Lope de Vega and Calderón, they had been forgotten; This recovery by Rojas Zorrilla also made him an innovator, combining the formal of Calderón with the truly tragic episodes of Seneca’s heroines.

[3] It’s as if in the last century we compared Woody Allen’s humor to that of Mel Brooks.