Hola amigos de nortonteattro.blog. Yo soy Nortan palacio, conocido artísticamente y en Alles is Drama como Norton P.

hello friend of nortonteatro.blog. I am Nortan Palacio, known artistically, and in Alles is Drama, as Norton P.

Lunes 4 marzo 2024.

ANÉCDOTA 1OO.

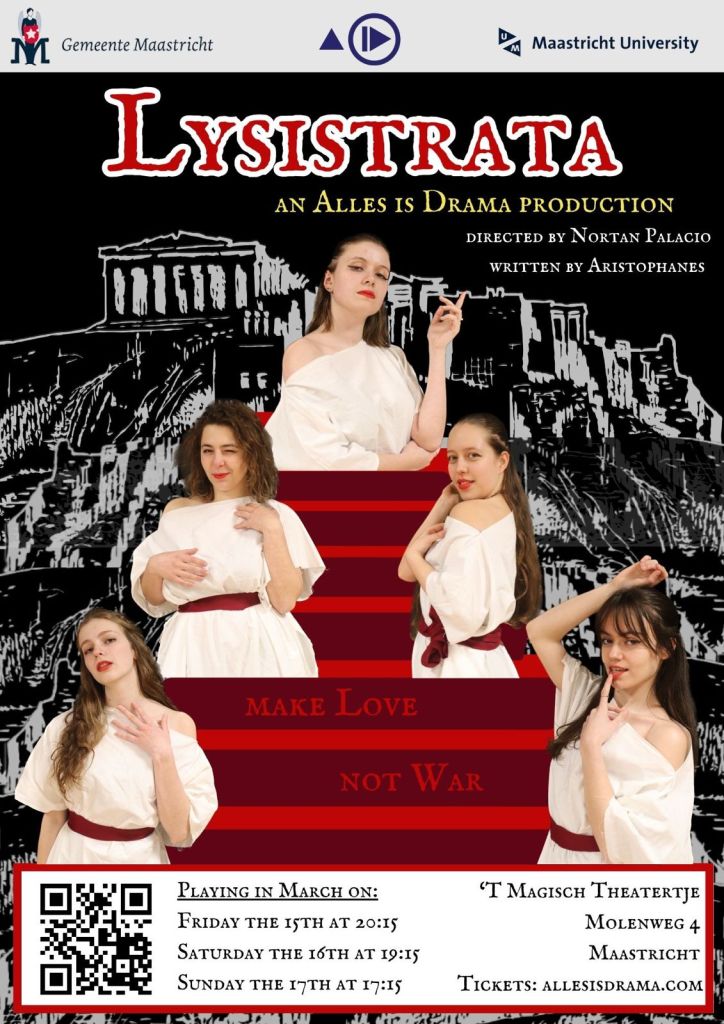

Como puede apreciarse en el título de la anécdota y en el cartel, soy el director de la comedia Lysistrata del Comediógrafo griego Aristófanes, para la compañía universitaria de Maastricht Alles is Drama, que se estrena el próximo 15 de marzo; y por eso he pensado que estas dos semanas estaré bastante ocupado con ensayos y ultimando cuestiones artísticas y técnicas, por lo tanto, no he tenido ni tendré tiempo para escribir las anécdotas de este blog. Lo siento.

Aunque luego he tomado otra decisión: ¿Y no será bueno hablar de esta obra, de su autor, del montaje y del mensaje del montaje? Ya sé; en el Mentidero de los Comediantes, hablo de teatro del Siglo de Oro Español, pero un desliz, sobre todo siendo yo el director del tal montaje, es perdonable. Además, si miras bien, lector, sabrás que esta anécdota es la numero 100 del blog y qué mejor que celebrarlo hablando de mi montaje y por tanto de mí mismo. Y si a esto le añadimos que así, además, le doy publicidad a la producción. (basta de excusas: que estas semanas[1]hablaré de Lisístrata y ya está)

ARISTÓFANES: ¿CREADOR DEL TEATRO POLÍTICO Y DEL TEATRO FEMINISTA?

A los que estudiamos teatro siempre nos dijeron que el Teatro Político fue una invención de Erwin Piscator, en la primera mitad del siglo XX, que lo hizo bajo una inspiración marxista, es decir que es un teatro que toma partido por los de abajo, que trasladó estos presupuestos a la teoría teatral en su libro El teatro político y que Bertolt Brecht, siguiendo estas coordenadas las llevó a las tablas con su Teatro Épico.

Pues yo te digo que no, primero porque el teatro siempre ha tenido un carácter de crítica política, pero es que en las obras de Aristófanes esa crítica aparece en primer plano, con hechos, lugares y personajes reales. Con nombres y apellidos criticaba a los políticos de su tiempo y les ponía un espejo en el que mirarse, sin que el reflejo recibido casi nunca fuera bueno. Aristófanes vivió los momentos más trepidantes de la historia política de la Grecia antigua: vivió la época de mayor esplendor de Atenas con Pericles, la guerra del Peloponeso que Atenas perdió con Esparta, con Alcibíades como protagonista, la implantación del régimen de los treinta tiranos y la restauración posterior de las libertades. Además, fue contemporáneo de Sócrates, de Sófocles y de Tucídides, y aunque un poco mayor, también fue contemporáneo de Aristóteles, Platón, Jenofonte y Eurípides. Cómo no iba a hablar de política en sus obras.

Pero es que como postulaba Piscator en su Teatro Político; Aristófanes ya tomaba partido por los desfavorecidos y se oponía a los excesos de los demagogos (gobernantes) que por lo regular eran corruptos y promotores de las guerras con el dinero público (cualquier parecido con lo que está ocurriendo hoy en día es pura coincidencia).

Y como si fuera poco, en sus comedias utilizaba elementos «distanciadores» para realizar esa crítica: el héroe era un personaje popular, los conflictos finalizaban con situaciones utópicas y los personajes y diálogos llegaban a ser tan alocados, burdos, «sobrereales» e inesperados que hacían que el espectador no perdiera conciencia de que estaba asistiendo a una representación; y si investigas un poco, lector avezado, te darás cuenta de que vienen a ser muchos de los presupuestos del supuesto Teatro Épico de Brecht, el discípulo de Piscator. Es decir que muchas de las características de este Teatro Político postulado en el siglo XX d.C. ya estaban en las comedias de Aristófanes en el siglo V a.C.[2]

En cuanto al Teatro Feminista, si lo concebimos como teatro que habla en favor del género femenino y no solo como teatro hecho por mujeres, tampoco se quedó atrás; entre las once comedias que conservamos tiene tres en las que las mujeres son protagonistas. En dos, ellas adquieren el poder político y solucionan los conflictos con mucha astucia, dejando al género masculino bastante mal parado. Estas son Lisístrata y La asamblea de las mujeres. En la primera las mujeres, de toda Grecia, hacen una huelga de abstinencia sexual para que los hombres (de las ligas de Atenas y Esparta) enfrentados en la Guerra del Peloponeso, se avengan a negociar la paz (pero eso lo desarrollaré más adelante). En La asamblea de las mujeres, las féminas toman el poder mediante un alocado golpe de Estado y en su asamblea disponen que todos los bienes materiales y corporales sean comunes (comunismo pre-Marx), cosa que al final consiguen, aunque de una manera menos efectiva que en Lisístrata. Luego también tiene otra comedia de mujeres en la que las damas atenienses celebran la fiesta de Deméter y Perséfone, Las Tesmoforias, aunque el tema es la fertilidad de la tierra y una crítica contra el autor de tragedias Eurípides, a quien Aristófanes criticaba en varias de sus obras.

El caso de las dos primeras debía ser algo increíble para los espectadores griegos, ya que las mujeres reales en Atenas, a pesar de ser una ciudad tan moderna, tenían un estatus social, cultural y económico bastante ínfimo, si exceptuamos a las meretrices. Y aunque en las tragedias había personajes femeninos tan fuertes y astutos (Medea o Fedra) como en estas comedias, ninguna de ellas conseguía su objetivo final sino con la muerte. En cambio, Lisístrata es el primer personaje femenino del Teatro Occidental en lograr sus objetivos finales, aun siendo estos de una importancia política tan desmesurada.

SINOPSIS DE LISÍSTRATA

Lisístrata convoca a las mujeres de Grecia a que se unan a ella en una huelga con la que obliguen a los hombres a negociar la paz[3]. La huelga consiste en la abstinencia sexual. Pero para añadir más presión, las mujeres toman la Acrópolis, con el tesoro público dentro, para que los hombres no tengan como costear la guerra. Después de muchas vicisitudes: el coro masculino intenta quemar la Acrópolis con las mujeres dentro, pero el coro de mujeres se lo impide; desde la Asamblea envían a un Magistrado con algunos guardas para amedrentarlas, pero ellas no se dejan y lo humillan; con el paso de los días las mujeres también sienten irrefrenables apetitos sexuales y flaquean por lo que Lisístrata tiene que inventarse una profecía dada por un oráculo y las vuelve convencer; finalmente Lisístrata (que en lengua griega antigua vendría significar: ‘la que disuelve los ejércitos’) y sus seguidoras logran que los hombres, con sus falos a punto de explotar, se comprometan a firmar la paz. Las mujeres, para celebrar el acuerdo, los invitan a una fiesta orgiástica dentro de la Acropolis y cuando acaba, los hombres deciden que, desde ese momento, cuando tengan que negociar asuntos políticos entre atenienses y espartanos solo lo harán después de haber bebido, comido y satisfecho sus deseos sexuales, para no volver a tener tentaciones de volver a luchar.

El lenguaje usado tanto por mujeres como por hombres está cargado de connotaciones sexuales y de acusaciones políticas absolutamente increíbles, que hoy llamaríamos ‘políticamente incorrectos’. Me río yo de los que hoy se jactan de usar terminología políticamente incorrecta como símbolo de modernidad y de rompedores. Eso lo invento Aristófanes hace veinticinco siglos, señores.

Con otros aspectos de mi montaje de Lisístrata para Alles is Drama, te espero la próxima anécdota, queridísimo lector.

[1] En esta anécdota hablaré de la obra y del autor y en la siguiente hablaré de la compañía universitaria Alles is Drama, de la dirección del montaje y del mensaje del montaje.

[2] En mi tesis doctoral: El teatro de Quevedo: una aproximación pragmática, estudié esta conexión entre Aristófanes, Piscator y Brecht, aunque haciéndola pasar por Quevedo y sobre todo con su única pieza dramática conservada: Cómo ha de ser el privado.

[3] En el momento en que se representó, se cree que en el 411 a.C. la Guerra del Peloponeso llevaba más de 20 años enfrentando a los ciudadanos de las ligas atenienses y espartanas. Cada liga englobaba varias ciudades.

ANECDOTE 1OO.

As you can see from the title of the anecdote, and in the flyer, I’m the director of the comedy Lysistrata by the Greek comedian writer Aristophanes, for the university company of Maastricht Alles is Drama, which premieres on March 15th; and that’s why I’ve thought that these two weeks I’ll be quite busy with rehearsals and finalizing artistic and technical issues. Therefore, I have not had and will not have time to write the anecdotes of this blog. I am sorry.

But then I made another decision: And wouldn’t it be good to talk about this work, its author, the production and the message of the performance? I know; in the Mentidero de los Comediantes I speak of theatre from the Spanish Golden Age, but a slip, especially since I am the director of such a production, is forgivable. Also, if you look closely, dear reader, you will know that this anecdote is the 100th of the blog, and what better way to celebrate it than by talking about my production and therefore about myself. And if we add to this the fact that I also give publicity to the production. (Enough excuses: these weeks[1]I’ll talk about Lysistrata and that’s it)

ARISTOPHANES: CREATOR OF POLITICAL THEATRE AND FEMINIST THEATRE?

Those of us who study theatre have always been told that Political Theatre was an invention of Erwin Piscator, in the first half of the 20th century, who did it under a Marxist inspiration, this means that this theatre takes the side of people from below, who transferred these presuppositions to theatre theory in his book Political Theatre and that Bertolt Brecht, following these coordinates, he brought them to the stage with his Epic Theatre.

Well, I say no, first because theatre has always had a character of political criticism, but in the works of Aristophanes that criticism appears in the foreground, with real facts, places, and characters. With names and surnames, he criticized the politicians of his time and put a mirror in which to look at themselves, without the reflection received being almost never good. Aristophanes lived through the most exciting moments in the political history of ancient Greece: he lived through the period of greatest splendour of Athens with Pericles, the Peloponnesian War that Athens lost with Sparta, with Alkibiades as the protagonist, the implementation of the regime of the thirty tyrants and the subsequent restoration of freedoms. In addition, he was a contemporary of Socrates, Sophocles, and Thucydides, and although a little older, he was also a contemporary of Aristotle, Plato, Xenophon, and Euripides. How could he not talk about politics in his works?

But as Piscator postulated in his Political Theatre; Aristophanes was already taking the side of the underprivileged and opposing the excesses of demagogues (rulers) who were usually corrupt and promoters of wars with public money (any resemblance to what is happening today is purely coincidental).

And as if that were not enough, in his comedies he used ‘distancing’ elements to make this critique: the hero was a popular character, the conflicts ended with utopian situations and the characters and dialogues became so crazy, crude, ‘overreal’ and unexpected that the audience did not lose awareness that he was attending a performance; and if you do a little research, seasoned reader, you will realize that they are many of the presuppositions of the supposed Epic Theatre of Brecht, the disciple of Piscator. That is to say, many characteristics of this Political Theatre postulated in the twentieth century A.D. were already in the comedies of Aristophanes in the fifth century B.C.[2]

As for Feminist Theatre, if we conceive it as theatre that speaks in favour of the female gender and not only as theatre made by women, he was not shabby either; among the eleven comedies that we have, there are three in which women are the protagonists. In two, they acquire political power and solve conflicts with great cunning, leaving the male gender in a rather bad light. These are Lysistrata and The Assembly of Women. In the first, women from all over Greece go on a sexual abstinence strike so that the men (from the leagues of Athens and Sparta) who were fighting in the Peloponnesian War agree to negotiate peace (but I will develop that later). In The Women’s Assembly, the women take power through a crazy coup d’état and in their assembly, they arrange that all material and bodily goods are common (pre-Marx communism), which in the end they achieve, although in a less effective way than in Lysistrata. Then he also has another comedy of women in which the Athenian ladies celebrate the feast of Demeter and Persephone, The Thesmophoria, although the theme is the fertility of the earth and a critique against the author of tragedies Euripides, whom Aristophanes criticized in several of his works.

The case of the first two, must have been something incredible for Greek viewers, since real women in Athens, despite being such a modern city, had a rather negligible social, cultural and economic status, if we except for prostitutes. And although in the tragedies there were female characters as strong and cunning (Medea or Phaedra) as in these comedies, none of them achieved their final goal except with death. On the other hand, Lysistrata is the first female character in Western Theatre to achieve her ultimate goals, even though they are of such disproportionate political importance.

SINOPSIS DE LISÍSTRATA

Lysistrata calls on the women of Greece to join her in a strike to force the men to negotiate peace[3]. The strike consists of sexual abstinence. But to add to the pressure, the women take over the Acropolis, with the public treasury inside, so that the men will not have the money to pay for the war. After many vicissitudes: the men’s choir tries to burn the Acropolis with the women inside, but the women’s choir prevents them; from the Assembly the male rulers send a magistrate with some guards to intimidate them, but the women do not allow themselves and humiliate him; As the days go by, women also feel irrepressible sexual appetites and falter, so Lysistrata has to invent a prophecy given by an oracle and convinces them again; finally, Lysistrata (which in ancient Greek would mean: ‘she who dissolves armies’) and her followers manage to get men, with their phalluses about to explode, to commit themselves to signing peace. The women, to celebrate the agreement, invite all men to an orgiastic party inside the Acropolis and when it ends, the men decide that, from that moment on, when they have to negotiate political matters between Athenians and Spartans they will only do so after they have drunk, eaten and satisfied their sexual desires, so as not to be tempted to fight again.

The language used by both, women and men, is loaded with sexual connotations and absolutely unbelievable political accusations, which today we would call ‘politically incorrect’. I laugh at those who today boast of using politically incorrect terminology as a symbol of modernity and ground breakers. That was invented by Aristophanes twenty-five centuries ago, gentlemen.

With other aspects of my staging of Lysistrata for Alles is Drama, I await the next anecdote, dearest reader.

[1] In this anecdote I will talk about the play and the author, and in the next one I will talk about the university company Alles is Drama, the direction of the production and the message of the performance.

[2] In my doctoral thesis: Quevedo’s Theater: A Pragmatic Approach, I studied this connection between Aristophanes, Piscator and Brecht, although passing it off as Quevedo, and especially with his only preserved dramatic piece: Cómo ha de ser el privado (How the Private Must Be)

[3] At the time it was performed, it is believed that in 411 BC the Peloponnesian War had been going on for more than 20 years between the citizens of the Athenian and Spartan leagues. Each league encompassed several cities.

¡Felicidades por estas masnificas 100 anécdotas!

Me gustaMe gusta

Gracias, amigo.

Me gustaMe gusta

Masnificas (más que magníficas)

Me gustaMe gusta