Hola amigos de nortonteatro.blog. Yo soy Nortan Palacio, conocido artísticamente, y en las comedias «de repente», como Norton P.

Hello friends of notontearo.blog. I am Nortan palacio, known artistically and, in the ‘improvised’ comedies, as Norton P.

Viernes 4 de noviembre 2023

ENGLISH VERSION: BELOW THE SPANISH VERSION

ANÉCDOTA 88

LOS DRAMATRUGOS SEGUNDONES EN EL SIGLO DE ORO ESPAÑOL: LUIS VÉLEZ DE GUEVARA II

Como decía en la pasada anécdota; Luis Vélez de Guevara fue un autor prolífico y, que se sepa, solo superado por Lope de vega en número de comedias escritas. Recordamos que escribió más de 400 obras y por el momento se conservan casi 100, digo por el momento, porque algunas veces hay hallazgos afortunados que nos aumentan el número de obras conservadas. Por ejemplo; en el famoso Catálogo Bibliográfico y Biográfico del Teatro Antiguo Español: desde sus orígenes hasta mediados del siglo XVII, ‒una obra titánica realizada por Cayetano Alberto de la Barrera y Leirado entre 1815 y 1872, y cuya visita a la edición digital de la Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, o cualquier otra edición, recomiendo‒ se recogía que se conservaban unas ochenta obras de Vélez de Guevara, sin embargo, hoy en día se han recuperado casi veinte más[1], con lo que, como digo, se cuenta con un repertorio de casi cien obras de nuestro dramaturgo.

En cuanto a su estilo y temas hay que decir que, como todos en su época, seguía el esquema estructural marcado por Lope de Vega, pero Vélez de Guevara lo adecuaba a su manera de concebir el teatro. Por ejemplo se movía en registros tan distantes como las comedias de disparates y comedias “de repente”; las comedias de santos, las de historia nacional, las de historia extranjera, las basadas en leyendas folclóricas y en temas del Romancero y en todos tuvo obras muy destacadas e incluso obras maestras. Además, se movía con genialidad por los mundos de los Autos Sacramentales y de los Entremeses.

También es notoria su concepción del escenario como instrumento para la escritura, se ve que conocía el teatro por dentro, así concebía algunas comedias de gran tramoya e impacto visual, en las que las acotaciones llegan a ser parte de la literatura dramática. Un ejemplo es la escena final de la comedia El primer Conde de Orgaz, en las que describe la escena del entierro de manera que parezca que estuviéramos viendo el famoso cuadro del Greco que se puede admirar en Toledo: “El entierro del Conde de Orgaz”

Finalmente, es también destacable la creación de caracteres femeninos impactantes que van desde las mujeres fuertes, incluso varoniles, a las discretas e inteligentes. Estos caracteres serían los que después desarrollarían Tirso de Molina y calderón de la Barca en sus más famosas obras.

Algunas de sus comedias «de repente» creadas para veladas teatrales en el Palacio real, pasaron a su novela El diablo cojuelo y conocemos otra que se titula: Juicio final de todos los poetas españoles muertos y vivos, cargadas de chistes, disparates y de juegos de ingenio.

Entre las obras de historia española encontramos: Más pesa el rey que la sangre; Pelayo y Covadonga; La luna de la sierra que tiene entre sus protagonistas a los Reyes Católicos, La batalla naval de Lepanto; El águila del agua y la más conocida: El diablo está en Cantillana, con Pedro primero el cruel como protagonista.

Entre estas de tema histórico quiero resaltar una titulada Don Pedro Miago, de 1613, que es una comedia que puede considerarse menor, pero que marcó un hito porque fue la primera vez que en el teatro se usó el estilo poético impulsado Luis de Góngora: «el Culteranismo», y con esto se dio un giro copernicano al teatro que solo imitaba a Lope de Vega y que fue el que, más adelante, generó el estilo que tuvo el nuevo reinado de Calderón de la Barca.

De las comedias que tratan leyendas folclóricas se destacan La niña de Gómez Arias sobre el cantar popular de una joven seducida y vendida como esclava, y que sería la inspiración para la comedia de mismo nombre de Calderón (que es la que más conocemos), también hay comedias de mujeres bandoleras como La montañesa de Asturias. Entre estas comedias de folclore hay una considerada obra maestra: La serrana de la Vera, donde Vélez nos muestra un prototipo de mujer dura -debido a que fue seducida y abandonada, se venga de los hombres: matando a todos con los que tenía relaciones sexuales: mas de 2000- que, como dije, tuvo bastante desarrollo en otras comedias de su época.

De las de temas bíblicos y religiosos las mejores son La hermosura de Raquel, la creación del mundo, La Magdalena, Santa Susana etc.

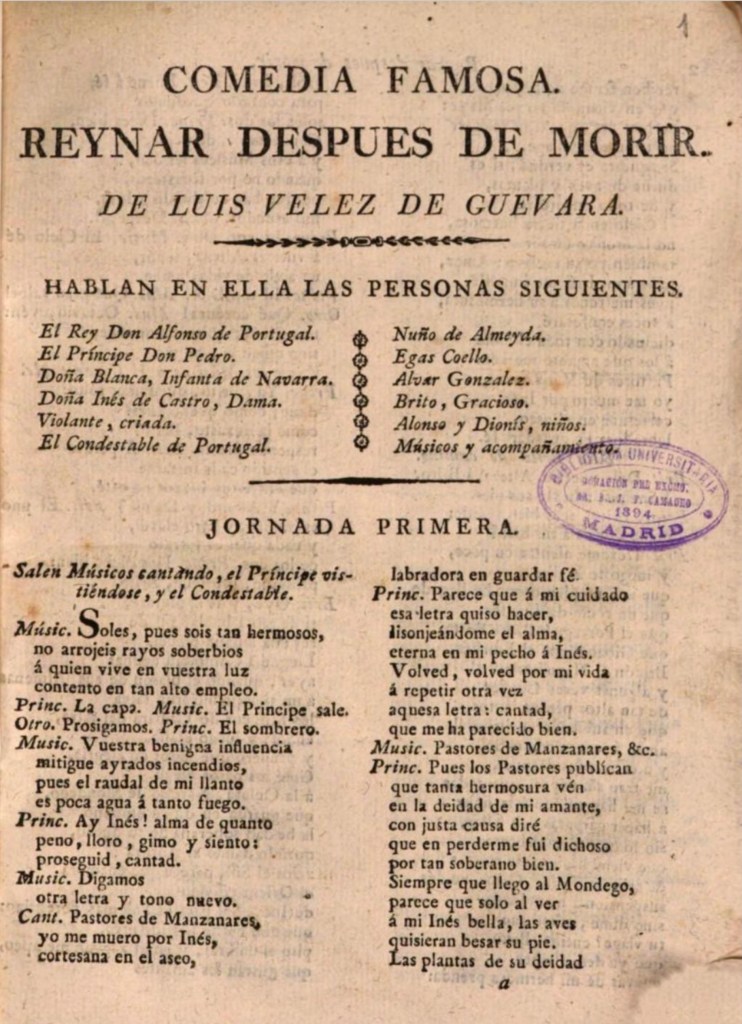

Entre las de Historia extranjera se destacan: Atila, azote de Dios, Tamerlán de Persia, Juliano el Apóstata, El príncipe esclavo, y hazañas de Scandenber. También entre estas tiene una obra maestra que es quizá la mejor comedia de Vélez de Guevara y una de las obras cumbre del teatro español: Reinar después de morir que escenifica la trágica vida de Inés de Castro[2]. Este tema, por su componente macabro, fue muy recurrente en la literatura Europea del Barroco[3], pero se dice que nadie trató el tema como nuestro autor. Así, por ejemplo, lo elogia José Luis García Barrientos para la Biografía de Vélez de Guevara que se puede leer en línea en la página de la Real Academia de la Historia:

Reinar después de morir, representada en Valencia en 1635 y publicada en Lisboa en 1652, es sin duda la obra maestra de Vélez y la versión más interesante de las muchas que, antes y después, se han hecho de los trágicos amores del príncipe don Pedro de Portugal y doña Inés de Castro. Los terribles sucesos aparecen envueltos en un clima de leyenda. En pocos dramas del repertorio el componente lírico se funde con la acción dramática de forma tan armoniosa. Los personajes rebosan emoción y verdad. La estructura raya en la perfección. Nada sobra ni falta en una trama tensa y bien acompasada, compuesta con estricta economía y soberana libertad. Bastarían tales logros para acreditar como dramaturgo de primer orden a Luis Vélez de Guevara; quien encarna a la perfección el tránsito entre una y otra cumbre del teatro aurisecular: procede de Lope y anuncia a Calderón.

Con este elogio a nuestro dramaturgo “mal llamado segundón”: Luis Vélez de Guevara, me despido por ahora, amigo lector, y te emplazo para la próxima semana con otro de ellos que a buen seguro nos sorprenderá.

[1] Por ejemplo: en 1994, el catedrático e investigador de la Universidad de Valladolid, Germán Vega Garcia-Luengos, uno de los mejores sabuesos de comedias perdidas del Siglo de Oro, dio a conocer un catálogo de Treinta comedias desconocidas de Ruiz de Alarcón, Mira de Amescua, Vélez de Guevara, Rojas Zorrilla y otros de los mejores ingenios de España. En este, recogía tres nuevas comedias de Vélez de Guevara: Correr por amor fortuna, El jenízaro de Albania y El mejor Rey en rehenes.

[2] Inés de castro era doncella de su prima Constanza quien viajaba a Coímbra para casarse con el infante don Pedro hijo del rey Alfonso IV de Portugal, pero cuando llegó la comitiva gallega de quién Pedro se prendó se prendó fue de Inés. Así, aunque el infante, aunque estaba casado con Constanza, mantenía amores con Inés y tuvieron algunos hijos ilegítimos. Cuando Constanza murió de un parto, Inés y Pedro tenían ocasión de casarse, pero Alfonso IV de Portugal repudiaba a Inés por sus amores extramaritales con Pedro y la hizo ejecutar. La leyenda cuenta que cuando, finalmente, el infante fue coronado como Pedro I, recuperó el cadáver de Inés, en avanzado estado de descomposición, la sentó en el trono e hizo que toda la corte portuguesa tuviera que rendirle pleitesías. De ahí el título «Reinar después de morir»

[3] El tema fue tratado por Lope de Vega, Jerónimo Bermúdez, Luis de Camoes, Luis Mejía de la Cerda, Aphra Behn, Madame de Genlis, y en el Cancionero Geral de Portugal, entre otros.

ANECDOTE 88

THE ‘SECOND’ PLAYWRIGHTS IN THE SPANISH GOLDEN AGE: LUIS VÉLEZ DE GUEVARA II

As I said in the last anecdote; Luis Vélez de Guevara was a prolific author and, as far as is known, only surpassed by Lope de Vega in the number of comedies written. As told before, he wrote more than 400 works and at the moment almost 100 are preserved. For the moment, because sometimes there are fortunate discoveries that increase the number of preserved works. For example, in the famous Bibliographic and Biographical Catalogue of the Old Spanish Theatre: from its origins to the mid-seventeenth century, – a titanic work made by Cayetano Alberto de la Barrera y Leirado between 1815 and 1872, to which I recommend a visit in the digital edition of the Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library, or any other edition – it was noted that some eighty works by Vélez de Guevara were preserved, However, today almost twenty more have been recovered[1], so, as I say, we have a repertoire of almost a hundred works by our playwright.

As for his style and themes, it must be said that, like everyone else in his time, he followed the structural scheme marked by Lope de Vega, but Vélez de Guevara adapted it to his way of conceiving the theatre. For example, he moved in registers as distant as comedies of nonsense and improvised comedies, the comedies about saints, those of Spanish history, those of foreign history, those based on folkloric legends, and themes of the Romancero, and in all of them he had very outstanding works and even masterpieces. Like the genius he is he also moved through the worlds of the Sacramental Plays and Entremeses.

In addition, his conception of the stage as an instrument for writing is notorious, it is clear that he knew the theater from the inside, so he conceived some comedies of great plot and visual impact, in which the annotations become part of the dramatic literature. An example is the final scene of the comedy The First Count of Orgaz, in which he describes the burial scene in such a way that it seems as if we were looking at the famous painting by El Greco that can be admired in Toledo: ‘The burial of Count of Orgaz’.

Finally, also noteworthy is the creation of striking female characters that range from the strong, even manly, to the discreet and intelligent women. These characters would later be developed by Tirso de Molina and Calderón de la Barca in their most famous works.

Some of his improvised comedies created for theatrical evenings in the Royal Palace, became part of his novel El diablo cojuelo and we know another one entitled Final Judgment of All the Spanish Poets Dead and Alive, full of jokes, nonsense and witty games.

Among the works of Spanish history we find Más pesa el rey que la sangre, Pelayo and Covadonga The Moon of the Sierra, which has the Catholic Monarchs among its protagonists, The Naval Battle of Lepanto, The eagle of the water and the best known of all, The devil is in Cantillana, with the King Pedro the first as the cruel protagonist.

Among these plays with a historical theme, I would like to highlight one entitled Don Pedro Miago, written in 1613, which is a comedy that can be considered minor, but which marked a milestone because it was the first time that the poetic style promoted by Luis de Góngora was used in the theatre: ‘Culteranismo’. With that a ‘Copernican turn’ was given to the theatre that was used to imitate Lope de Vega and that later generated the ‘new reign’ of Calderón de la Barca.

Of the comedies that deal with folkloric legends stand out: La niña de Gómez Arias, about the popular song of a young woman seduced and sold as a slave, that was to become the inspiration for the comedy with the same name by Calderón (which is the best known). There are also comedies of bandit women such as La montañesa de Asturias. Among these folklore comedies there is one considered a masterpiece: La serrana de la Vera, where Vélez shows us a prototype of a tough woman who takes revenge on men because she was seduced and abandoned, by killing everyone she had sex with, more than 2000 men. As I said earlier, it had a lot of influence in other comedies of his time.

Of those with biblical and religious themes, the best are The Beauty of Rachel, The Creation of the World, The Magdalena, Saint Susanna; etc.

Among those about Foreign History are Attila, Scourge of God, Tamerlane of Persia, Julian the Apostate, The Slave Prince, and Scandenber’s Deeds. Also among these is a masterpiece that is perhaps the best comedy of Vélez de Guevara and one of the best in all Spanish theatre, Reinar después de morir (Reing After Dying), which stages the tragic life of Inés de Castro[2]. This theme, due to its macabre components, was very recurrent in European literature of the Baroque[3], but it is said that no one treated the subject as our author did. Thus, for example José Luis García Barrientos praises him for the Biography of Vélez de Guevara, which can be read online on the website of the Royal Academy of History:

“Reinar después de morir (Reign After Dying), performed in Valencia in 1635 and published in Lisbon in 1652, is undoubtedly Vélez’s masterpiece and the most interesting of the many versions that, before and since, have been made of the tragic loves of Prince Don Pedro of Portugal and Doña Inés de Castro. The terrible events are shrouded in a climate of legend. In few dramas in the repertoire does the lyrical component merge with the dramatic action so harmoniously. The characters are brimming with emotion and truth. The structure borders on perfection. Nothing is superfluous or lacking in a tense and well-paced plot, composed with strict economy and sovereign freedom. Such achievements would suffice to accredit Luis Vélez de Guevara as a playwright of the first order; who perfectly embodies the transition between one summit of the Ausycenian theatre and another: he comes from Lope and announces Calderón”.

With this praise to our playwright misnamed ‘seconded’: Luis Vélez de Guevara, I say goodbye for now, dear reader, and I will summon you for next week with another of them that will surely surprise us.

[1] For example: in 1994, the professor and researcher at the University of Valladolid, Germán Vega Garcia-Luengos, one of the best sleuths of lost comedies of the Golden Age, released a catalogue of Thirty Unknown Comedies by Ruiz de Alarcón, Mira de Amescua, Vélez de Guevara, Rojas Zorrilla and other among the main geniuses in Spain. In it he collected three new comedies by Vélez de Guevara: Correr por amor fortuna, El janiszaro de Albania and El mejor Rey en rehenes.

[2] Inés de Castro was the maid of her cousin Constanza who was traveling to Coimbra to marry the Infante Don Pedro, son of King Alfonso IV of Portugal. But when the Galician entourage arrived, the one Pedro fell in love with was Inés. Thus, although the infant was married to Constanza, he had an affair with Inés and they had some illegitimate children. When Constance died of childbirth, Inés and Pedro had the opportunity to marry. But Alfonso IV of Portugal repudiated Inés for her extramarital affairs with Pedro and had her executed. Legend has it that when the infante was finally crowned as Pedro I, he recovered the corpse of Inés, in an advanced state of decomposition, seated her on the throne and made the entire Portuguese court pay homage to her. Hence the title «Reign After Dying»

[3] The subject was dealt with by Lope de Vega, Jerónimo Bermúdez, Luis de Camoes, Luis Mejía de la Cerda, Aphra Behn, Madame de Genlis, and in the Cancionero Geral de Portugal, among others.