Hola amigos de nortonteatro.blog. Yo soy Nortan Palacio, conocido artísticamente, y en el Museo Nacional del Teatro de España, como Norton p.

I AM HERE IN THE NATIONAL THEATRE MUSEUM, ON TOP IN PHOTO SESIÓN FOR THE CARTEL OF THE DRAMATIZED VISIT TO THAT MUSEUM (WHICH I CO-WROTE) AND ON BOTTON I AM JUST BEFORE ENTERING TO INVESTIGATE FOR THIS LAST BLOG POSTS.

Viernes 26 de mayo 2023.

ENGLISH VERSION: SEE BELOW THE SPANISH VERSION

ANÉCDOTA 79 LA COFRADÍA DE NUESTRA SEÑORA DE LA NOVENA: PRIMER SINDICATO DE ACTORES DE ESPAÑA III.

Venimos diciendo, en las pasadas anécdotas, que la Cofradía de Nuestra Señora de la Novena se constituyó como el primer sindicato de actores en Madrid, aunque después, como veremos, pasó a ser el sindicato de todos los actores de España y, cosa curiosa, todavía hoy sigue estando en la dicha Iglesia de San Sebastián. Hoy en día ya no funciona como sindicato, pero el hecho de que todavía conserve algunos de sus cofrades y siga realizando la celebración religiosa por el día de la Virgen, es de admirar.

Gracias a esos cofrades se han conservado todos los archivos de la Institución, aunque han sido depositados, como debe ser, en el Museo Nacional del Teatro de España que se encuentra en la localidad de Almagro[1]. Esa documentación nos ha permitido conocer mucho de las actividades teatrales y de las idas y venidas de los actores, actrices, empresarios, músicos, bailarines y dramaturgos de España, casi hasta nuestros días (siglo XX). Hoy en día, la Unión de Actores es el sindicato de actores por excelencia y sus labores son las de un sindicato como tal, sin ninguna connotación religiosa.

Pero como esta sección es un Mentidero, y queremos saber cosas de las gentes del Teatro de aquel Siglo de Oro Español, nos hemos ido a ese Museo Nacional del Teatro de España y nos hemos empapado de esa documentación. Y aunque tenemos que admitir que es copiosa y aquí no queremos saber las cosas administrativas, sino las que tienen enjundia de «chismes»; os vamos a presentar los datos más curiosos (sabrosos) de todos esos archivos.

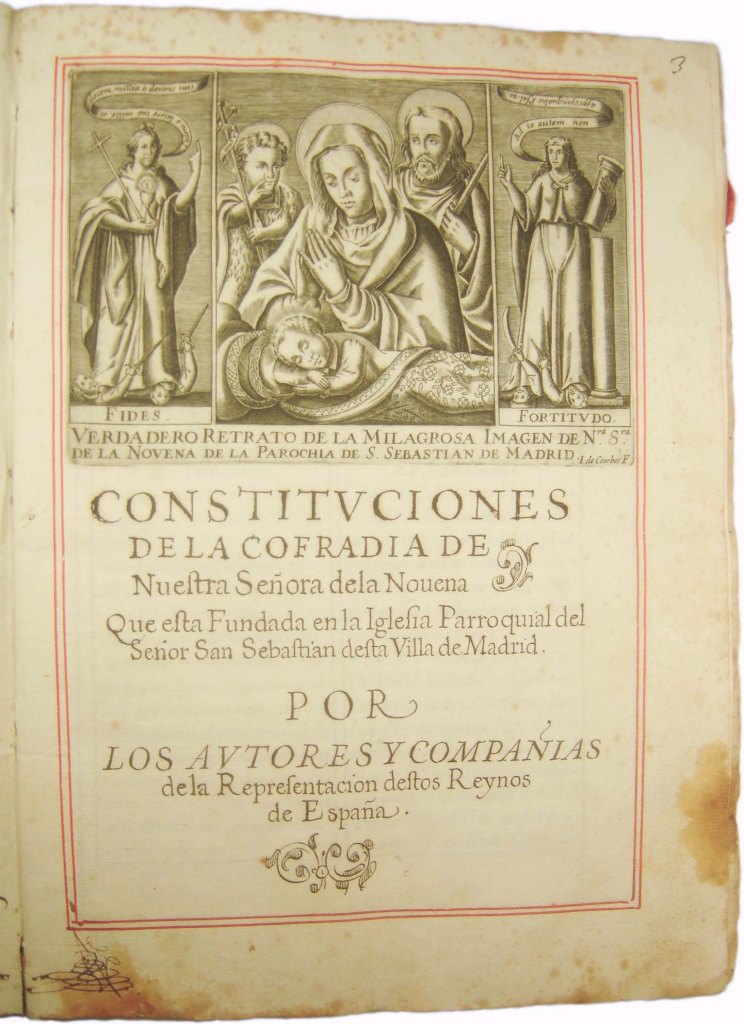

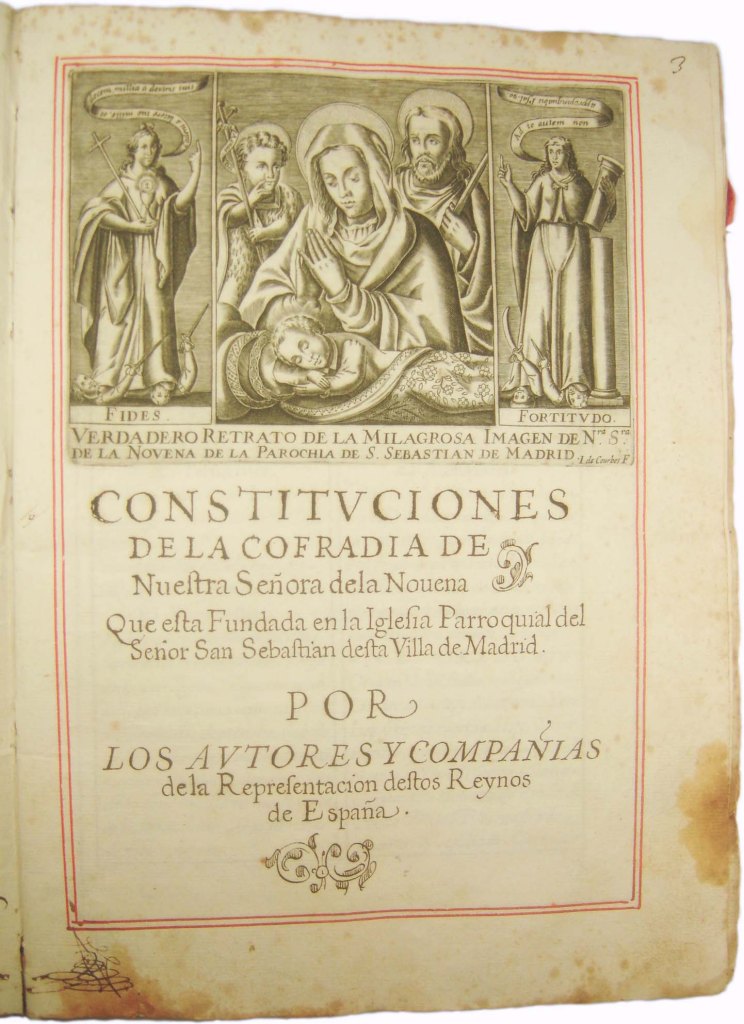

El documento más atractivo es el que con la Aprobación por parte del Consejo por Cardenal Infante don Fernando arzobispo de Toledo de la fundación del Gremio de Representantes. Pero es un manuscrito difícil de escudriñar, por sus formas arcaicas y una letra nada clara. Por eso debemos agradecer la labor del Grupo de Investigación Teatral DICAT que, bajo la dirección de Teresa Ferrer Valls, han descifrado, transcrito y digitalizado ese imponente manuscrito; puesto que de allí será desde donde os traeremos, amigos lectores, los artículos que consideremos de interés.

Los primeros folios dan cuenta de las obligaciones de los buenos cristianos, y los actores querían demostrar que lo eran: cómo debían rezar, cuándo debían oír misa, cuántas veces al año habían de confesarse, los 10 mandamientos, etc. Después viene lo tocante a la elección y las obligaciones de la junta directiva: los mayordomos, el tesorero, el secretario, los oficiales. Finalmente, aparece lo relativo a los cofrades, que serían todos los «socios» del Sindicato, es decir todos los actores y empresarios así como sus esposas (aunque estas no fueren del gremio teatral) e hijos no casados. Pero se dispuso una cláusula para ayudar, si fuese necesario, a los familiares no directos. Cosa bastante admirable.

Aquí empezamos a encontrar ciertas curiosidades tales como que las compañías (en principio las compañías de título) tenían ciertas obligaciones como elegir entre sus componentes a los cobradores que serían los encargados de recolectar las raciones que cada cofrade (actor o empresario) debía abonar a la Cofradía. También tenían que elegir a los enfermeros que serían como una especie de médicos que estarían siempre con ellos por si hubiese accidentes y heridos tanto en mitad de las representaciones, como en los ensayos, giras, etc.

Después, en el segundo título describe la obligación de aceptar y registrar (asentar en la lista de cofrades) a todos los representantes de España, incluidos los Cómicos de la Legua, buen punto de esta constitución; puesto que estos Cómicos de la Legua, por su condición ambulante y su consideración social: se los percibía como pequeños delincuentes y por tanto, no podían llegar a un pueblo sin avisar, sino que tenían que acampar a una legua de cada población (de ahí su denominación), antes de pedir los permisos oficiales para las representaciones, eran los más pobres. Con esta premisa de la constitución la Cofradía también se ayudaría a este sub-gremio más desvalido.

También hay puntos novedosos como el que los trabajadores de las compañías, aunque no fuesen cómicos ni empresarios, sino que tuviesen cargos menores como mozos del servicio o guardarropas, también pudieran convertirse en cofrades aunque no tendrían voz ni voto en las reuniones de la Cofradía.

Por otro lado, encontramos puntos algo absurdos, en los que se obliga a los actores y empresarios, ya asentados como cofrades, a que no pudieran tomar esposa, esposo o compañeros si los tales no aceptaban convertirse en cofrades. Es como si hoy en día no te dejaran pertenecer a un sindicato si tu familia no quisiera pertenecer al tal sindicato.

El tercer título se refiere a las cuotas (según la dicha constitución: limosnas) que los Cofrades deberían pagar, desde el primer punto encontramos algo importante y que hoy en día se ha perdido en los sindicatos como tales; estas aportaciones tenían un carácter progresivo: es decir que el que más ganaba más aportaba. Se estableció que cada cofrade que fuera actor o mozo de servicios debía aportar un cuarto de cada diez reales que ganara (esto equivalía a cuatro maravedís de la moneda de Castilla de aquella época), y que los «autores» (volvemos a recordar que eran los empresarios o dueños de las compañías) tendrían que aportar un real cada vez que la compañía representara una obra. Luego, era bien que cuando enfermaba, moría o enviudaba un cofrade que fuera pobre (por ejemplo un cómico de la legua) tendría unas ayudas similares a la de los cofrades más ricos.

Y, finalmente, también encontramos curiosidades como que los actores que faltaran a un ensayo tenían que pagar una multa y esa multa pasaría directamente a las arcas de la Cofradía, o que en las puertas de los Corrales de Comedias, cada vez que hubiera representación, se pusieran limosneros con cestos y lo recaudado también pasaría a la Cofradía.

Como puede apreciarse la pela es la pela.

Nos vemos la próxima semana.

[1] El hecho de que el Museo Nacional del Teatro de España se encuentre en Almagro, pequeña localidad manchega de solo 9000 habitantes, y no en Madrid o Barcelona como sería lo esperable, se debe a que actualmente se considera a Almagro la Capital del Teatro en España, puesto que allí se descubrió, en los años cincuenta del siglo XX, la estructura completa de un Corral de Comedias, lo que le dio a esta pequeña villa, un estatus teatral impensable. Primero se convocó un Festival de Teatro que rápidamente se hizo internacional Festival Internacional de Teatro Clásico de Almagro, con tanto atractivo que se tuvieron que crear más espacios teatrales (hoy en día es la localidad con más butacas teatrales por habitantes que se conoce en el mundo) aunque el festival solo tenía (tiene) actividad un mes del verano (primero era en agosto y ahora es en julio). En aras a rellenar ese tiempo restante que constituye un largo año, en 1994 se instituyó una compañía que le dio vida, tanto al Corral de Comedias como a la localidad convirtiéndola en atractivo teatral, durante los meses de la primavera, de parte del verano y del otoño; esa Compañía era Corrales de Comedias Teatro. Un servidor se considera orgullosísimo de haber sido uno de sus fundadores y haber trabajado en ese espacio (Catedral del Teatro podríamos llamarlo) durante casi 25 años. Por todo esto, El fundador y alma del Museo, Andrés Peláez, se obstinó con que la sede el Museo nacional del Teatro Español debía estar en Almagro y lo logró.

ANECDOTE 79 THE BROTHERHOOD OF OUR LADY OF THE NOVENA: FIRST TRADE UNION FOR ACTORS IN SPAIN III.

In the past anecdotes, I said that the Brotherhood of Our Lady of the Novena was established as the first Trade Union for Actors in Madrid, although later, as we will see, it became the union for all the actors in Spain and, curiously, it is still situated in the earlier mentioned Church of San Sebastián. Today it does no longer function as a union, but the fact that it still retains some of its brothers and continues to carry out the religious celebration for the day of the Virgin, is to be admired.

Thanks to these brothers, all the archives of the Institution have been preserved, although they have been deposited, as it should be, in the National Theatre Museum of Spain located in the town of Almagro[1]. This documentation made it possible to learn much about the theatre activities and the comings and goings of actors, actresses, producers, musicians, dancers, and playwrights of Spain, almost to present day (twentieth century). Today, the Union of Actors is the trade union de actors in Madrid, and its tasks are those of a modern trade union, without any religious connotations.

But as this blog is a ‘Mentidero’, and we want to know about the people of the Theatre of the Spanish Golden Age, I went to the National Museum of the Theatre of Spain, and I extracted all relevant documentation. And although I should mention that the archive is copious, except for those parts that have the substance of ‘gossip’, administrative topics were not interesting for this blog. I will present the most intriguing (tasty) facts I found in those files.

The most attractive document is the one that records the approval by the Council by Cardinal Infante Don Fernando archbishop of Toledo of the foundation of the Guild of Actors. But it is a difficult manuscript to examen, because of its archaic forms and unclear handwriting. That is why we must thank the work of the DICAT Theatre Research Group which, under the direction of Teresa Ferrer Valls, has deciphered, transcribed and digitized this imposing manuscript, since from that I will bring you, dear readers, the articles that I consider of interest.

The first pages give an account of the obligations of good Christians, because the actors wanted to show that they were: how they should pray, when they should attend Holy Mass, how frequently they should go for confession, the 10 commandments, etc. Then, comes the election and duties of the board of directors: the guardians, the treasurer, the secretary, the administrators. Finally, there is what was related to the brothers, who were all the ‘members’ of the Union, that is, all the actors and producers as well as their wives (although they were not member of the theatre guild) and their unmarried children. But, quite admirably there was also a clause which, if necessary, provided for help to non-immediate relatives.

Here I started to find certain interesting things such as that the companies (in principle the official companies) had certain obligations such as choosing the collectors who would oversee the collecting of the fees that each colleague (actor or producer) had to pay to the Brotherhood, from among their members. They also had to choose the nurses who were something like doctors, and who would always be with the members in case there were accidents and/or injuries, either in the middle of the performances, or during rehearsals, tours, etc.

Then, the second chapter describes the obligation to accept and register (in the list of brothers) all the actor of Spain, including the Comics de la Legua, which was a great point of this organization. Since these Comedians of the League, due to their wandering lifestyle and their social level they were very poor: they were perceived as petty criminals and therefore, they needed special permission before they could enter a town, and they had to camp a league (3 miles) from each village (hence their name), before asking for the official permit for their performances. Based on this statement in the charter the Brotherhood also helped this very vulnerable sub-guild.

There are also novelties such as the fact that the workers in the companies, even if they were not comedians or producers, but had minor positions such as waiter or cloakroom assistant, could also become brothers although they did not have a voice or vote in the meetings of the Brotherhood.

However, I also found now somewhat absurd sounding items, by which actors and producers, who were already established as brothers, were not allowed to take a wife, husband or partner in case they did not want to become brothers. It is as if in the present time one would not be allowed to belong to a trade union if your family didn’t also want to be a member of that union.

The third chapter refers to the dues (according to the said charter: alms) that the Brothers had to pay. From the first item there is something important which today has been lost in trade unions: These contributions were a progressive in character, that is, the one who earned the most, also contributed most. It was established that each Brother, whether they were actor or waiter had to contribute a quarter of every ten reales he earned (this was equivalent to four maravedís in the currency of Castile of that period), and that the ‘authors’ (remember again that they were the entrepreneurs and owners of the companies) would have to contribute a real each time the company performed a theatre play. It was good that when a poor Brother, such as a comedian of the league, got sick, died, or became widowed, he or she received similar aid as the richest Brothers.

And, finally, I also found peculiarities such as that actors who missed a rehearsal had to pay a fine which would go directly to the coffers of the Brotherhood. Also, at every representation, there would be baskets at the doors of the Corrales de Comedias to put tips that also went to the Brotherhood.

As you can see money is money is money.

See you next week.

[1]The fact that the National Theatre Museum of Spain is located in Almagro, a small town in La Mancha with only 9000 inhabitants, and not in Madrid or Barcelona as would be expected, is due to the fact that Almagro is currently considered the Capital of Theatre in Spain, because in the fifties of the twentieth century, the complete structure of a Corral de Comedias, , was discovered which gave this small village, an unthinkable status in the theatre world. First, a Theatre Festival was organized that quickly became the International Festival of Classical Theatre of Almagro, with so much attraction that more theatrical spaces had to be created. It is also the town with most theatre seats per inhabitant in the world. Because the festival only lasts one month in the summer (first it was in August and now it is in July), to fill the remaining time of the long years, in 1994 a company was founded that gave life, both to the Corral de Comedias and to the town, turning it into a theatre attraction, during the months of spring, part of summer and autumn. The Company was called Corrales de Comedias Teatro. As a member of the company, I consider myself very lucky to have been one of its founders, and to have worked in that space (we could call it the Cathedral of the Theatre) for almost 25 years. For all this, the founder and soul of the Museum, Andrés Peláez, insisted that the headquarters of the National Museum of Spanish Theatre should be in Almagro, and he succeeded.