Hola amigos de nortontearo.blog. yo soy Nortan Palacio, conocido artísticamente y entre las lágrimas panegíricas por la muerte del doctor Juan Pérez de Montalbán, como Norton P.

Hello friends or nortonteatro.blog. I am Nortan palacio, known artistically, and between the eulogy tears for the death of Juan Pérez de Montalbán, as Norton P.

Viernes 1 dicembre 2023.

ENGLISH VERSION: BELOW SPANISH VERSION

ANÉCDOTA 91

LOS DRAMATRUGOS SEGUNDONES EN EL SIGLO DE ORO ESPAÑOL:

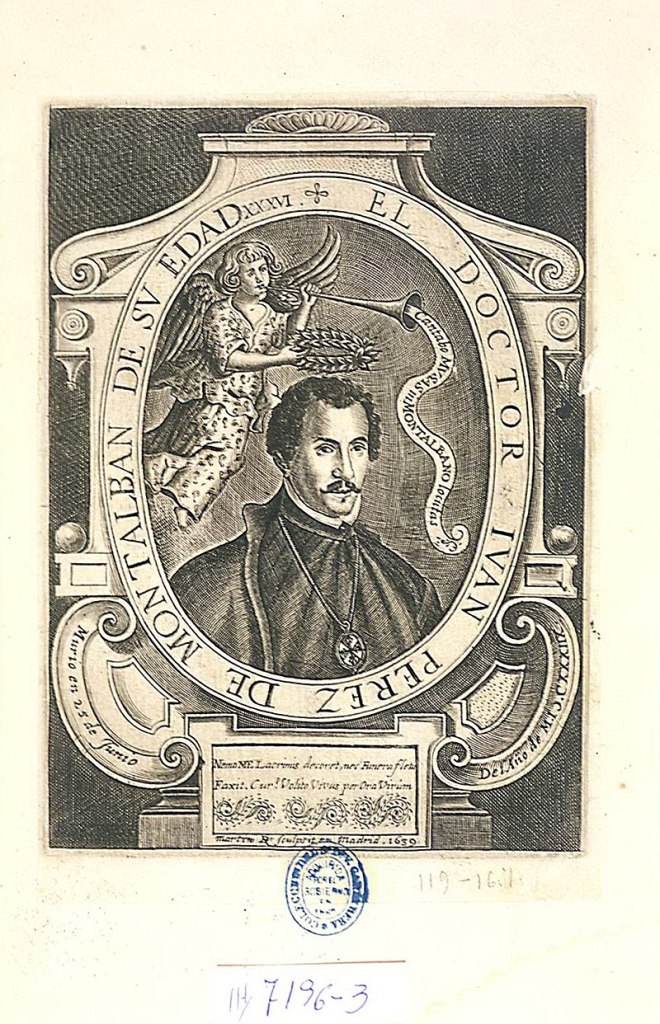

JUAN PÉREZ DE MONTALBÁN

Me atrevo a decir que el dramaturgo del que vamos a tratar en esta anécdota fue realmente un segundón, pero no porque su calidad dramática fuera menor, sino porque se dedicó fervorosamente a su profesión religiosa[1] y en sus escritos cultivó otros géneros literarios que le granjearon más fama. Algunos de sus escritos por ser éxitos de ventas, rediciones y traducciones y otros por otros menesteres que luego mencionaremos, pero que son los primeros a los que se retrotraen, los que lo conocen, cuando en los círculos académicos se menciona a Juan Pérez de Montalbán.

Revisemos primero su biografía: Juan Pérez de Montalbán nació en Madrid en 1602 y murió en la misma ciudad en 1638. Tristemente murió joven y quizá por eso no nos legó más comedias, dramas o autos sacramentales.

Su padre Álvaro Pérez era editor, así que nuestro dramaturgo desde niño estuvo rodeado de libros y se codeó con muchos de los grandes literatos de aquella espectacular época, por eso también fue muy aficionado a la lectura y a la investigación de cosas de todo tipo. Pero, gracias a que su padre tenía el privilegio especial para editar todas las obras de Lope de Vega y era muy buen amigo suyo, la carrera literaria de Juan Pérez de Montalbán está mas o menos supeditada a la del Fénix de los ingenios.

Nuestro dramaturgo estudió filosofía y humanidades en la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, donde alcanzó el grado de licenciado en 1617. Después, en la misma universidad, se doctoró en teología en 1625, ese mismo año alcanzó las ordenes sacerdotales y fue nombrado capellán de la iglesia de San Juan en Ocaña. Un año más tarde ingresó en la congregación de Clérigos naturales de Madrid, en 1633 fue nombrado discreto de la Venerable Tercera Orden de San Francisco y en 1634 fue elegido notario de la Inquisición. Así transcurrió la vida eclesiástica de nuestro autor, que terminó en 1638. No se le conocen escándalos de amores o descendencia, por lo que, ya lo dije, suponemos que fue respetuoso de su profesión.

En el tiempo que le quedaba libre se dedicaba a investigar sobre todas las materias conocidas, a escribir y a frecuentar los círculos literarios de Madrid. Parece que no se daba un respiro en su afán de saber y muchos dicen que eso fue lo que propició la enfermedad mental que lo llevó tan joven a la tumba; algunos de sus amigos, que escribieron poemas fúnebres a su muerte, lo insinúan[2]. Por ejemplo, Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla lo llamó: «Mártir ya de su mismo entendimiento».

Otros, dicen que su enfermedad empezó a manifestarse en 1635 justo en el año en que murió Lope de Vega. A Pérez de Montalbán le dolió tanto su muerte, que dedicó todo su tiempo en aquel momento en la preparación de un homenaje en forma de libro que le dedicó a su maestro: Fama póstuma a la vida y muerte del Doctor Frey Lope de Vega Carpio en 1636 (la primera biografía que se escribió sobre el Fénix de los ingenios y la que fue tomada como modelo por todos los investigadores y biógrafos posteriores), en la que invirtió tanto tiempo y esfuerzo que unidos al dolor por la muerte de su mentor terminaron por matarle.

Sin embargo, parece que la causa medica más probable era que sufría una enfermedad genética puesto que dos de sus cuatro hermanos no superaron la infancia; su madre quedó ciega a temprana edad y una de sus hermanas que era monja también presentaban cuadros de locura crónica y alucinaciones.

Como mencionaba, su vida estuvo unida a la de Lope de vega en muchas maneras; por ejemplo, gracias a esta primera biografía, Pérez de Montalbán casi siempre es citado cuando se cita la vida de Lope de Vega, así que conociendo la ingente cantidad de investigaciones, libros, biografías, artículos, ediciones de comedias y otras obras, etc. que tratan o están dedicados a Lope; así es la cantidad de veces que se encontrará el nombre de Pérez de Montalbán.

Además, la primera obra de teatro de Pérez de Montalbán que subió a las tablas de los Corrales de Comedias, en 1619, cuando este tenía solo diecisiete años: Morír y Dismular, se debió al empeño de Lope por ayudar a su discípulo a triunfar en el teatro. el Fénix también le dedicó a nuestro dramaturgo la obra La francesilla, publicada en 1620.

Respecto a esta amistad también cabe mencionar que en 1624 Pérez de Montalbán publicó un poema titulado Orfeo en lengua Castellana, criticando el poema gongorino (culterano): Orfeo que había publicado Juan de Jáuregui. Se dice que el poema tiene una calidad que no sería atribuible a Pérez de Montalbán y por eso muchos creen que en realidad lo escribió Lope de Vega y puso el nombre de su discípulo, para que la polémica entre culteranos y anticulteranos no se avivara más.

En cuanto a las obras teatrales, también la sombra de Lope lo cobija, tenemos que decir que quizá injustamente, pero de ello hablaremos en la próxima anécdota, de momento me limitaré a decir que escribió unas cincuenta comedias y diez autos sacramentales y que algunas alcanzaron bastante éxito.

Entre las obras no dramáticas que le dieron fama, tenemos una colección de novelas cortas (ejemplares) llamada Sucesos y prodigios de amor, llena de goces carnales que no se esperarían que salieran de la pluma de un sacerdote como este; entre las cuales, como cité, hay alguna prohibida por la Inquisición; la titulada La mayor confusión por lo escandaloso de un incesto de una madre con un hijo que después tienen una hija que al crecer se convierte en esposa de quien es su hermano y padre. Si es verdad que era confusión, pero también nos muestra que lo de creernos libertinos, no debe considerarse cosa nueva.

Finalmente, quiero hablarles de su obra más famosa: Para todos. Y no por lo buena que es (no es mala) sino porque que produjo una nueva polémica literaria, esta vez con Francisco de Quevedo, otro que parecía que las compraba. Pero el tiempo y espacio no me quieren dar más, querido lector, por lo que te apremio para que en la próxima anécdota nos divirtamos con esta polémica que dejo abierta y con los detalles de las obras dramáticas de nuestro Juan Pérez de Montalbán.

[1] Esto lo estoy diciendo, refiriéndome estrictamente a su vida personal, ya que entre sus escritos, aparecían personajes depravados y situaciones sexuales escabrosas que llevaron a la misma Inquisición a censurar algunas de ellas.

[2] En un homenaje póstumo editado por un su amigo: Pedro Grande de Tena que se titula: Lágrimas panegíricas a la temprana muerte del gran poeta y teólogo insigne Doctor Juan Pérez de Montalbán en 1639.

ANECDOTE 91

THE SECOND PLAYWRIGHTS IN THE SPANISH GOLDEN AGE:

JUAN PÉREZ DE MONTALBÁN

I dare say that the playwright we are going to deal with in this anecdote was really second-rate, but not because his dramatic quality was less, but because he devoted himself fervently to his religious profession[1] and in his writings cultivated other literary genres that earned him more fame. Some of his writings because they were bestsellers, editions and translations and others because of other tasks that we will mention later, but which are the first to be taken back to, those who know him, when Juan Pérez de Montalbán is mentioned in academic circles.

Let’s first review his biography: Juan Pérez de Montalbán was born in Madrid in 1602 and died in the same city in 1638. Sadly, he died young, and perhaps that’s why he didn’t bequeath us any more comedies, dramas or sacramental autos.

His father Álvaro Pérez was a publisher, so our playwright was surrounded by books since he was a child and rubbed shoulders with many of the great writers of that spectacular time, so he was also very fond of reading and researching things of all kinds. But, thanks to the fact that his father had the special privilege of editing all the works of Lope de Vega and they were really good friends, Juan Pérez de Montalbán’s literary career is more or less subordinated to that of the Lope.

Our playwright studied philosophy and humanities at the University of Alcalá de Henares, where he obtained his degree in 1617. Later, at the same university, he received his doctorate in theology in 1625, that same year he was ordained a priest and appointed chaplain of the church of San Juan in Ocaña. A year later he entered the congregation of native clerics of Madrid, in 1633 he was appointed discreet of the Venerable Third Order of St. Francis and in 1634 he was elected notary of the Inquisition. Thus passed the ecclesiastical life of our author, which, as we have said, ended in 1638. He is not known to have any love scandals or offspring, so, as I said, we assume that he was respectful of his profession.

In the time he had left, he devoted himself to researching all known subjects, to writing, and to frequenting the literary circles of Madrid. It seems that he did not give himself a break in his eagerness to know and many say that was what led to the mental illness that took him so young to the grave; Some of his friends, who wrote funeral poems at his death, hint at this[2]. For example, Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla called him: «Martyr of his own understanding.»

Others say that his illness began to manifest itself in 1635, the very year that Lope de Vega died. Pérez de Montalbán was so pained by his death that he devoted all his time at that time to the preparation of a tribute in the form of a book that he dedicated to his master: Posthumous Fame to the Life and Death of Doctor Fra’ Lope de Vega Carpio in 1636 (the first biography written about the Phoenix of the Geniuses and the one that was taken as a model by all subsequent researchers and biographers). In which he invested so much time and effort that, together with the pain of his mentor’s death, they ended up killing him.

However, it seems that the most likely medical cause was that he suffered from a genetic disease since two of his four siblings did not survive infancy; Her mother became blind at an early age and one of her sisters, who was a nun, also exhibited chronic insanity and hallucinations.

As he mentioned, his life was linked to that of Lope de Vega in many ways; for example, thanks to this first biography Pérez de Montalbán is almost always cited when the life of Lope de Vega is cited, so knowing the enormous amount of research, books, biographies, articles, editions of comedies and other works, etc. that deal with or are dedicated to Lope; such is the number of times Pérez de Montalbán’s name will be found.

In addition, the first play by Pérez de Montalbán that took to the stage of the Corrales de Comedias, in 1619, when he was only seventeen years old: Morír y Dismular, was due to Lope’s determination to help his disciple succeed in the theater. the Phoenix also dedicated the play La francesilla to our playwright, published in 1620.

Regarding this friendship, it is also worth mentioning that in 1624 Pérez de Montalbán published a poem entitled Orfeo in the Castilian language, criticizing the poem Gongorino (culterano): Orfeo that had been published by Juan de Jáuregui. It is said that the poem has a quality that would not be attributable to Pérez de Montalbán and that is why many believe that it was actually written by Lope de Vega and named after his disciple, so that the controversy between culteranos and anticulteranos would not be further fueled.

As for the other theatrical works, Lope’s shadow also covers him, I have to say that perhaps unfairly, but we will talk about it in the next anecdote, for the moment I will limit myself to saying that he wrote about fifty comedies and ten sacramental plays and that some of them were quite successful.

Among the non-dramatic works that made him famous, we have a collection of short novels called Sucesos y prodigios de amor (Events and Prodigies of Love), full of carnal pleasures that would not be expected from such a priest as this; among which, as I mentioned, there is one forbidden by the Inquisition; the one entitled The Greatest Confusion Because of the scandal of an incest of a mother with a son who later has a daughter who, when she grows up, becomes the wife of her brother and father. It is true that it was confusion, but it also shows us that believing ourselves to be libertine should not be considered something new.

Finally, I want to talk to you about his most famous work: For Everyone. And not because of how good it is (it’s not bad) but because it produced a new literary polemic, this time with Francisco de Quevedo, another who seemed to buy them. But time and space do not want to give me more, dear reader, so I urge you to have fun in the next anecdote with this controversy that I leave open and with the details of the dramatic works of our Juan Pérez de Montalbán.

[1] I am saying this, referring strictly to his personal life, since among his writings, there were depraved characters and lurid sexual situations that led the Inquisition itself to censor some of them.

[2] In a posthumous homage edited by his friend: Pedro Grande de Tena that is entitled: Lágrimas panegíricas a la prematura muerte del gran poeta y teologo Doctor Juan Pérez de Montalbán (Eulogy tears for the premature death of the great theologist Juan pérez de Montalbán) en 1639.