Hola amigos de nortonteatro.blog. Yo soy Nortan Palacio, conocido artísticamente, y en las Academias Burlescas, como Norton P.

Hello friends of notontearo.blog. I am Nortan palacio, known artistically and in the Burlesque Academies as Norton P.

Viernes 28 de octubre 2023.

ENGLISH VERSION: BELOW SPANISH VERSION.

ANÉCDOTA 87

LOS DRAMATRUGOS SEGUNDONES EN EL TEATRO DEL SIGLO DE ORO ESPAÑOL: LUIS VÉLEZ DE GUEVARA I

Mientras investigo para las entradas de estas últimas anécdotas me reafirmo en la teoría de que estos dramaturgos son ¨mal llamados segundones” y el caso de Vélez de Guevara es uno de los que más me da la razón.

Resulta que al parecer escribió más de 400 comedias de las que se conservan alrededor de 100. Esto quiere decir que después de Lope de Vega fue el dramaturgo más prolífico de aquella época (escribió bastantes más comedias que Calderón -120- y unas cuantas más que Tirso de Molina -casi 400) y por lo tanto uno de los más prolíficos del teatro de todos los tiempos y lugares, que se sepa. Esto no significa que cantidad y calidad sean sinónimos, pero también quiere decir que de las 500 escritas habrá algunas que puedan considerarse obras maestras y otras obras de calidad importante, como luego veremos, y esto es algo que también pasa con el corpus dramático de Lope de Vega.

Pero por qué a Luis Vélez de Guevara se le olvidó, por qué no se le ha estudiado tanto como a Lope de Vega; sabiéndose, como se sabe, que en algún momento fueron los dos dramaturgos mejor valorados por los espectadores de su época. La explicación puede tener varias razones.

Primero, porque al parecer fue alguien mas modesto que Lope y no se daba tanto autobombo, ni estaba metido en todas las disputas literarias de la época, sino que, también lo comentaremos más adelante, era muy apreciado por sus colegas de profesión.

Segundo, porque no se encargó de que su teatro fuera editado antes de morir como sí hicieron, Lope, Tirso de Molina, Calderón de la Barca, Ruíz de Alarcón, Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla, e incluso el mismo Cervantes que escribió poco teatro pero lo dejó editado y aunque su teatro fue olvidado; al momento de su renacimiento en el siglo XIX, fue fácil recuperarlo. En cambio el Teatro de Vélez de Guevara circuló en manuscritos y pliegos sueltos, hasta la segunda mitad del siglo pasado en que algunos investigadores se interesaron por él, como C. George Peale, que desde 1997 está editando sus comedias en (vaya por Dios) Los Estados Unidos.

Finalmente, porque Luis Vélez de Guevara es conocido por la única obra que escribió en prosa: la novela (o mejor llamarla fantasía satírica) El Diablo Cojuelo. Considerada la mejor obra satírica de su época después de las de Quevedo. Y que aunque no es una obra teatral, por sus poros se destila mucho teatro; entre otras cosas porque se la dedica irónicamente a los Mosqueteros[1] y les dice que es la única vez que escribe sin miedo a que ellos puedan silbarlos y patalearlo en los Corrales; y porque entre sus misceláneas páginas también encontramos entremeses o academias burlescas[2].

Así pues, una vez explicada la valoración de nuestro dramaturgo de esta semana, vamos a hablar de su trayectoria vital, de la que también, hasta no hace mucho, se conocía poco, y dejaremos para la próxima anécdota el estudio de sus obras teatrales.

Luis Vélez de Guevara nació en Écija, provincia de Sevilla en 1579, su nombre de pila era Luis Vélez de Santander, aunque luego contaré por qué cambió su segundo apellido; sus padres eran Diego Vélez de Dueñas y su madre Francisca Negrete de Santander. Se graduó en artes (otro más) en la Universidad de Osuna, una universidad menor, se sabe que allí estudió becado por ser pobre y se concluye que por esta razón no fue a una Universidad Mayor a hacerse Licenciado.

Sin embargo, sin ser de familia importante, ni tener estudios especializados, ni haberse hecho adulto en Madrid, debió de contar con suerte, o quizá medró bien, y toda su trayectoria profesional estuvo ligada a nobles o a la familia real. Con 19 años entró a servir como paje de Rodrigo de Castro que era el Cardenal Arzobispo de Sevilla y gracias a eso pudo viajar a Madrid en 1598 a la entronización de Felipe III y en 1599 a Valencia a las bodas de este mismo monarca con Mariana de Austria; en esos lugares, además de ser testigo de los grandes acontecimientos socio-políticos, pudo conocer a los literatos más importantes del momento, como a Lope de Vega, a quién conoció en Valencia y con el que siempre, sorprendentemente y conociendo a Lope, mantuvo una buena amistad.

En 1600, debido a la muerte del Cardenal entró a servir al conde de Fuentes, quien fue nombrado gobernador de Milán y se fue a Italia como soldado hasta 1602, al volver a España decidió probar suerte en Valladolid, donde se había trasladado la Corte y también la cohorte de artistas de la época. Allí se codeó con todos ellos, puesto que en 1603 escribió un soneto laudatorio para los preliminares del libro de Agustín de Rojas: El viaje entretenido y en 1604 otro soneto para el prólogo de las Rimas de su ya buen amigo Lope de Vega. En Valladolid, debió empezar su carrera de dramaturgo, puesto que la primera obra escrita por él, de la que se tiene noticia de que fue estrenada fue El cerco de Roma por el rey Desiderio, en Salamanca en 1606.

Ese mismo año la corte, el rey, los funcionarios y los literatos volvieron a Madrid y Luis Vélez de Guevara se trasladó con ellos a la ciudad donde alcanzaría la gloria y terminaría sus días. Debido a sus intentos de escalar en la corte se cambió el segundo apellido de “Santander” a “Guevara”, ya que según cuenta uno de sus hijos, Juan Vélez de Guevara, (que también fue poeta y dramaturgo) quiso poner por delante el orgullo ser descendiente de Llorente Vélez de Guevara uno de los trescientos hidalgos que, llevados de Ávila por Alfonso X el Sabio, ganaron la plaza de Jerez de la Frontera. No se sabe si en realidad era descendiente del tal hidalgo, pero lo que sí parece cierto es que el apellido “Santander” tenía olor a judío converso, puesto que la inquisición había ajusticiado a un tal Luis de Santander en Écija en 1554. Y ya se sabe que en la Corte para ascender había que demostrar ser cristiano viejo.

Pero siempre estaba en aprietos económicos y cambiando de amos como personaje de novela picaresca; en estos tiempos fue secretario del conde de Saldaña Diego Gómez de Sandoval y del marqués de Peñafiel Juan Téllez de Girón. Pero todos sus amos morían o caían en desgracia en la Corte. A la muerte de Felipe III y la coronación de Felipe IV, con su poderoso valido el conde-duque de Olivares, quien le tenía aprecio, parecía que la suerte le iba cambiar y contó con cargos importantes pero también de poca duración: primero en 1623 fue nombrado ujier de cámara nada menos que del príncipe de Gales, que había llegado a Madrid para contraer nupcias con la hermana de Felipe IV, la infanta María, pero esta lo rechazó por no ser católico y el futuro Carlos I regresó a Inglaterra sin esposa y sin ujier.

Después fue nombrado Mayordomo del archiduque Carlos de Austria quien llegó a Madrid en noviembre de 1624 y nuestro dramaturgo creyó ver sus problemas económicos resueltos, pero a los pocos días el archiduque murió de un atracón (la comida española que es muy sabrosa, aunque debe ser tomada en su justa medida) y dejó a Vélez de Guevara otra vez en la inopia.

Por último en 1625 le llegó el cargo que ostentaría casi hasta su muerte: ujier de cámara del rey, pero tenía un inconveniente: no recibía paga alguna (aunque algunas prebendas: posada, alimentos y médicos de la Corte) hasta no entrar en oficio (oficialmente), cosa que no sucedió hasta 1635, nueve años antes de morir. Por lo que podemos decir que toda su vida pasó penurias económicas.

Estas penurias eran incrementadas porque su vida sentimental fue azarosa, si bien, no como la de Lope de Vega, pero bastante, podríamos decir, plena. Se casó tres veces y tuvo algunos otros romances por lo que el número de hijos era considerable y los mantenía a todos, además de a la esposa de turno y a algunas de las amantes. Y como de lo que se ganaba con las comedias no se podía mantener a tanta gente; le tocaba elogiar a los grandes nobles para que le ayudaran económicamente. De ahí que en Madrid empezaron a llamarle “el poeta pedigüeño” o “el importuno Lauro”. No obstante, al final de su vida, con el cargo de ujier oficial, con lo que ganaba de las comedias y con una asignación de 200 reales mensuales que Felipe IV le dio ‒al parecer como compensación porque Vélez de Guevara ayudaba al monarca a corregir las comedias que escribía‒, vivió dignamente sus últimos días.

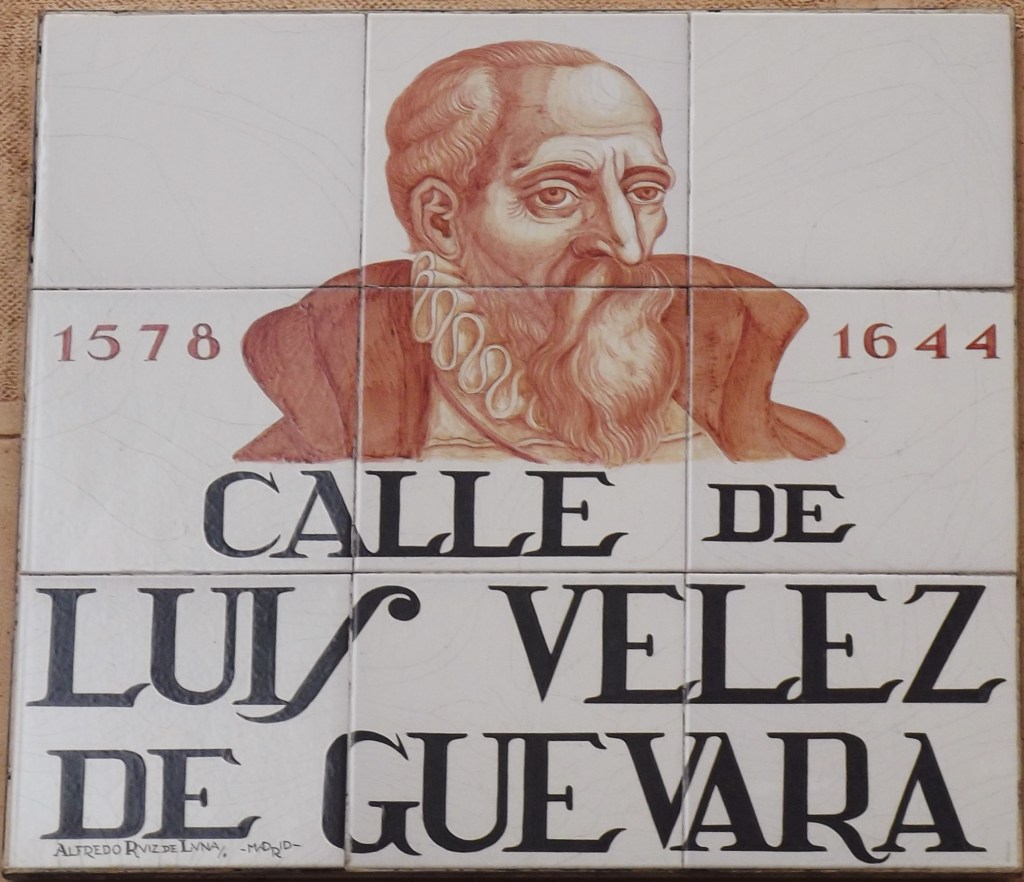

En 1642 cedió el título vitalicio de ujier a su hijo Juan y se retiró a su casa de la calle Urosas (que hoy en día se llama Calle de Luis Vélez de Guevara en el Barrio de Las Letras) al lado de su última esposa María López de Palacios. Dos años más tarde en 1644, y a los 65 años, increíblemente fue padre por última vez y ese mismo año murió de “unas calenturas y un aprieto de orina”.

Por los Avisos de Pellicer sabemos que a su entierro, aunque no fue tan multitudinario como el de Lope de Vega asistieron “cuantos grandes señores y caballeros hay en la Corte”.

En la siguiente anécdota te hablaré, querido lector, del estilo dramático de nuestro poeta, de sus mejores obras y ahondaremos en su fama en los escenarios en su tiempo, que no fue poca, y en cómo esta se fue diluyendo con los siglos.

Hasta la próxima semana.

[1] Los hombres que asistían a los Corrales de Comedias (a los que se llamaba mosqueteros porque solían ir armados con mosquetes, que era el arma más utilizada en la época y casi todos los hombres la podían llevar) y que eran muy importantes en el éxito o el fracaso en el estreno de una comedia ya que con sus aplausos si les gustaba o silbidos y pataleos si no les agradaba; condicionaban el numero de asistentes a las siguientes representaciones y, así, la valoración del dramaturgo. Hay que tener en cuenta que las gentes iban a los Corrales a “ver y oír las comedias”. El trabajo de los dramaturgos era muy valorado en la época

[2] Las Academias Burlescas eran unas representaciones parateatrales, donde dos literatos se enfrentaban improvisando versos de burlas el uno al otro, y donde se valoraba la facilidad para crear lo versos, a veces de calidad impresionante. Estas representaciones las protagonizaban algunos de los mejores poetas, normalmente para deleite de la familia real.

ANECDOTE 87

THE SECONDED PLAYWRIGHTS IN THE SPANISH GOLDEN AGE: LUIS VÉLEZ DE GUEVARA I

While I am researching for the entries of these last anecdotes, I reaffirm the theory that these playwrights are «wrongly called seconded» and the case of Vélez de Guevara is one of the ones that proves me most right.

It turns out that he apparently wrote more than 400, of which about 100 of them have survived. This means that after Lope de Vega he was the most prolific playwright of that time (Calderón wrote 120 and Tirso de Molina almost 400) and, therefore one of the most prolific theatre playwrights of all times and places, as far as we know. This does not mean that quantity and quality are synonymous, but it also means that of the more of 400 written there will be some that can be considered masterpieces and others of important quality, as we will see later, and this is something that also happens with the dramatic corpus of Lope de Vega.

But why Luis Vélez de Guevara was forgotten, why has he not been studied as much as Lope de Vega; if it is known, as is known, that at some point they were the two best playwrights valued by the spectators of their time. There may be several reasons for this.

First, because it seems that he was someone more modest than Lope and did not give himself so much self-aggrandizement, nor was he involved in all the literary disputes of the time, but, we will also comment later, he was highly appreciated by his colleagues in the profession.

Second, because he did not see to it that his dramas was published before his death as Lope, Tirso de Molina, Calderón de la Barca, Ruíz de Alarcón, Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla did, and even Cervantes himself who wrote little theatre but left it published and although his theatre pieces was forgotten; at the time of its revival in the nineteenth century, it was easy to recover it. On the other hand, the comedies de Vélez de Guevara circulated in manuscripts and loose sheets, until the second half of the last century when some researchers became interested in it, such as C. George Peale, who since 1997 has been editing his comedies in the United States.

Finally, because Luis Vélez de Guevara is known for the only work he wrote in prose: the novel (or better call it satirical fantasy) El Diablo Cojuelo. It is considered the best satirical work of that time after Quevedo’s. And that although it is not a theatrical work, a lot of theatre is distilled through its pores; among other things because he ironically dedicates it to the Musketeers[1] and tells them that it is the only time he writes without fear that they might whistle and kick him in the Corrales; and because among his miscellaneous pages we also find entremeses or burlesque academies[2].

So, once we have explained the assessment of our playwright this week, we are going to talk about his life trajectory, of which also, until recently, he was unknown, and we will leave the study of his plays for the next anecdote.

Luis Vélez de Guevara was born in Écija, province of Seville in 1579, his given name was Luis Vélez de Santander, although I will later tell you why he changed his second surname; his parents were Diego Vélez de Dueñas and his mother Francisca Negrete de Santander. He graduated in arts (another one) at the University of Osuna, a minor university, it is known that he studied there on a scholarship because he was poor and it is concluded that for this reason he did not go to a major university to get a degree.

However, without being from an important family, or having specialized studies, or having become an adult in Madrid, he must have been lucky, or perhaps he prospered well, and his entire professional career was linked to nobles or the royal family. At the age of 19 he began to serve as a page to Rodrigo de Castro, who was the Cardinal Archbishop of Seville, and thanks to that he was able to travel to Madrid in 1598 for the enthronement of Philip III and in 1599 to Valencia for the wedding of this same monarch with Mariana of Austria; in those places, in addition to witnessing the great socio-political events, he was able to meet the most important writers of the time, such as Lope de Vega, whom he met in Valencia and with whom he always, surprisingly and knowing Lope, maintained a good friendship.

In 1600, due to the death of the Cardinal, he entered the service of the Count of Fuentes, who was appointed governor of Milan and went to Italy as a soldier until 1602, when he returned to Spain he decided to try his luck in Valladolid, where the Court and also the cohort of artists of the time had moved. There he rubbed shoulders with all of them, since in 1603 he wrote a laudatory sonnet for the preliminaries of Agustín de Rojas’s book: El viaje entretenido, and in 1604 another sonnet for the prologue of the Rimas of his already good friend Lope de Vega. In Valladolid, he must have begun his career as a playwright, since the first play written by him, which is known to have been premiered, was The Siege of Rome by King Desiderio, in Salamanca in 1606.

That same year the court, the king, the officials and the literati guys returned to Madrid and Luis Vélez de Guevara moved with them to the city where he would achieve glory and end his days. Due to his attempts to climb the court, his second surname was changed from «Santander» to «Guevara», because according to one of his sons, Juan Vélez de Guevara, (who was also a poet and playwright) he wanted to put pride ahead of being a descendant of Llorente Vélez de Guevara, one of the three hundred noblemen who, brought from Ávila by Alfonso X the wise, they won the square of Jerez de la Frontera. It is not known if he was actually a descendant of the nobleman, but what does seem certain is that the surname ‘Santander’ had the smell of a converted Jew, since the Inquisition had executed a certain Luis de Santander in Écija in 1554. And it is well known that in order to be promoted at Court you had to prove that you were an old Christian.

But he was always in financial straits and changing masters like a character in a picaresque novel; at this time he was secretary to the Count of Saldaña, Diego Gómez de Sandoval, and to the Marquis of Peñafiel, Juan Téllez de Girón. But all his bosses died or fell from grace at Court. On the death of Philip III and the coronation of Philip IV, with his powerful validator the Count-Duke of Olivares, who was fond of him, it seemed that his luck was going to change and he had important but also short-lived positions: first in 1623 he was appointed usher of the chamber to, none other than, the Prince of Wales. that he had come to Madrid to marry Philip IV’s sister, the Infanta Maria, but she rejected him because he was not Catholic and the future Charles I returned to England without a wife and an usher.

Later he was appointed Steward of the Archduke Charles of Austria who arrived in Madrid in November 1624 and our playwright thought he saw his economic problems solved, but a few days later the Archduke died of a binge (Spanish food that is very tasty, although it must be taken in its proper measure) and left Vélez de Guevara again in the dark.

Finally, in 1625, he received the position he would hold almost until his death: usher of the king’s chamber, but he had a drawback: he did not receive any pay (although some perks: inn, food and doctors from the Court) until he entered the office (officially), which did not happen until 1635, nine years before he died. So we can say that all his life he went through economic hardships.

These hardships were increased because his sentimental life was eventful, although not like that of Lope de Vega, but quite full, we could say. He married three times and had a few other affairs, so the number of children was considerable and he supported them all, as well as the wife of the day and some of the mistresses. And since it was not possible to keep so many people from what was earned from comedies; It was his turn to praise the great nobles to help him financially. Hence, in Madrid they began to call him «the poet of Beggar» or «the importunate Lauro». However, at the end of his life, with the position of official usher, with what he earned from the comedies and with an allowance of 200 reales per month that Philip IV gave him – apparently as compensation because Vélez de Guevara helped the monarch to correct the comedies he wrote – he lived his last days with dignity.

In 1642 he gave the lifetime title of usher to his son Juan and retired to his house on Calle Urosas (which today is called Calle de Luis Vélez de Guevara in the Barrio de Las Letras) next to his last wife María López de Palacios. Two years later in 1644, and at the age of 65, he incredibly became a father for the last time and that same year he died of «a fever and a squeeze of urine».

From Pellicer‘s Notices we know that his funeral, although it was not as multitudinous as that of Lope de Vega, was attended by «all the great lords and gentlemen there are at Court».

In the following anecdote I will tell you, dear reader, about the dramatic style of our poet, his best works and we will delve into his fame on the stage in his time, which was not little, and how it was diluted over the centuries.

See you next week.

[1]The men who attended the Corrales de Comedias ( who were called musketeers because they used to be armed with muskets, which was the most used weapon at the time and almost all men could carry it) and who were very important in the success or failure in the premiere of a comedy since with their applause if they liked it or whistles and kicks if they did not like it; they conditioned the number of attendees to the following performances and, thus, the evaluation of the playwright. It must be borne in mind that people went to the Corrales to «see and hear the comedies». The work of playwrights was highly valued at the time

[2] The Burlesque Academies were paratheatrical performances, where two writers confronted each other improvising verses of mockery, and where the ease of creating the verses, sometimes of impressive quality, was valued. These performances were performed by some of the best poets, usually to the delight of the royal family.